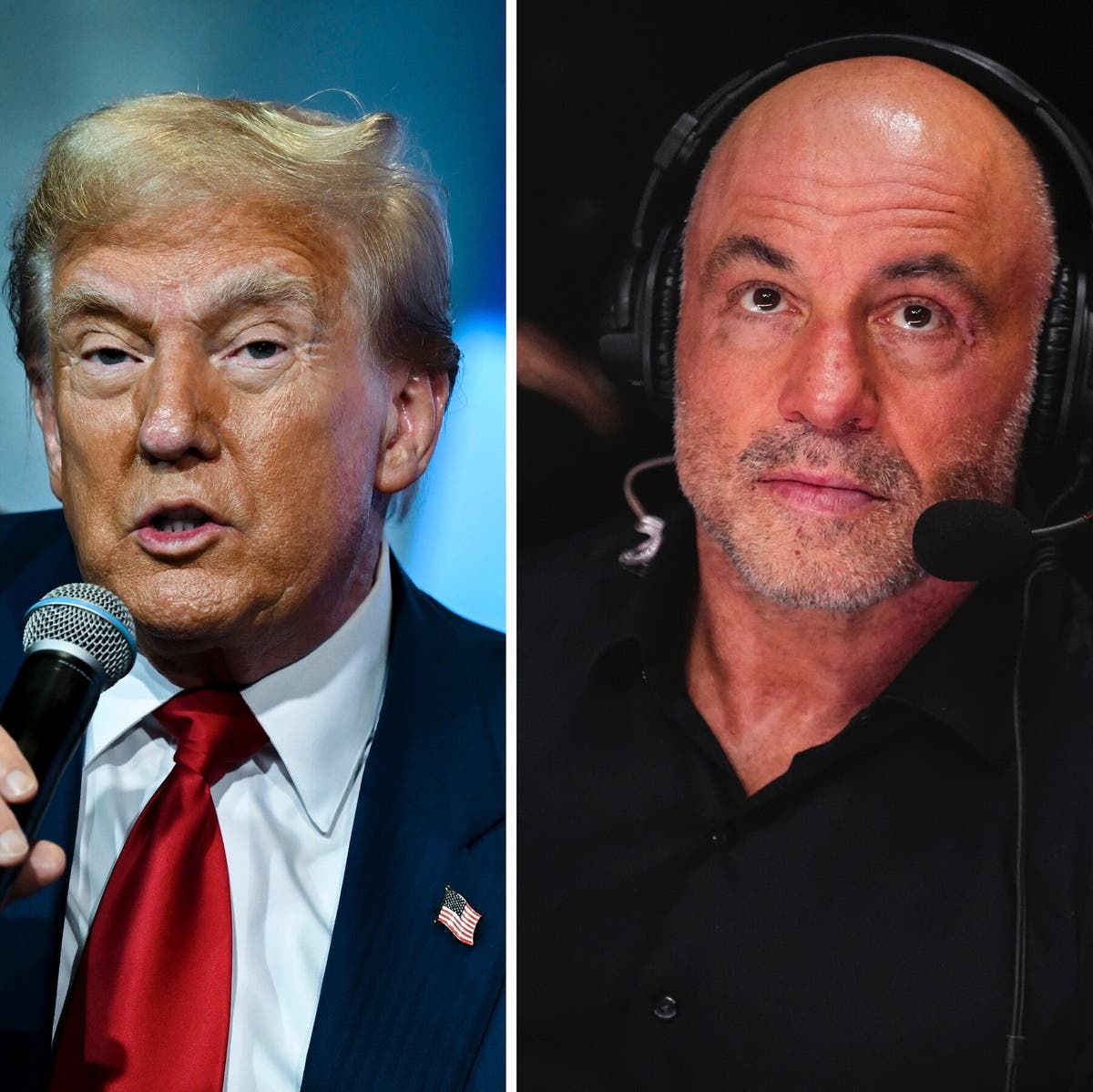

If Trump wins the election, this is what’s at stake for US foreign policy

When Americans choose between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris next month, the decision will mark one of the most consequential elections for US foreign policy in generations that could ripple out into conflicts and redraw alliances around the world. With the candidates deadlocked in the final polls before election day, just tens of thousands of…

When Americans choose between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris next month, the decision will mark one of the most consequential elections for US foreign policy in generations that could ripple out into conflicts and redraw alliances around the world.

With the candidates deadlocked in the final polls before election day, just tens of thousands of voters could decide whether world leaders next year face an American centrist in the vein of Joe Biden or a second term of office for one of the most disruptive US politicians of the last century.

The elections come at a moment when foreign leaders have appealed for American leadership and diplomacy, as Israel fighting wars in Gaza and Lebanon risks spiraling into a full-scale regional conflict with Iran, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine faces further potential escalation with reports of North Korean troops being sent to the front lines, a civil war in Sudan rages on for a second year, and there are warnings of growing trade and military competition between the US and China.

Trump’s brand of America First politics has already sown instability among both partners and adversaries; Nato countries say that never before has the US been seen as the “unpredictable ally”, a country where instability around the elections is the norm and the alliance’s long-term plans must be “Trump-proofed”.

Ahead of the elections, European diplomats in Washington have expressed dismay with the Biden administration’s cautious foreign policy, especially in relation to Ukraine and the White House’s failed efforts to conclude a ceasefire in Gaza, while also steeling themselves for the very real potential for a Trump victory and the instability that would inject into world politics.

“I can’t say for sure whether [Trump] would seek a deal with Putin on day one or whether he would drop a nuclear bomb on Moscow,” one European ambassador said about Trump. “The truth is that it’s a black box and that anyone who tells you that they know what’s going on inside [his] administration is lying.”

Last month, Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrived in Washington to vastly different receptions. At the White House he received a warm greeting in public, but privately officials responded skeptically to his “victory plan” against the Russian invasion and refused to grant his request to use US-made missiles to strike targets deep inside of Russia.

Then he met Donald Trump, who sought to humiliate Zelenskyy as he met him at Trump Tower in a hastily-arranged summit at the tail end of a visit to the United Nations.

“We have a very good relationship,” Trump said as Zelenskyy looked on stoically. “And I also have a very good relationship – as you know – with President Putin. And I think if we win, I think we’re going to get it resolved very quickly.”

“It takes two to tango, you know,” Trump added.

Meanwhile, diplomats from around the world continue to sit down with Trump and foreign policy thinkers rumoured to be tapped for his team, including with the authors of policy briefs from conservative think tanks such as the Heritage Foundation or the Trump-adjacent America First Policy Institute.

“Countries around the world are hedging and they have to be prepared for either outcome,” said Andrew Weiss, vice-president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former director for Russian, Ukrainian and Eurasian Affairs on the national security council staff. “The Washington professional foreign policy establishment look at the possibility of Trump’s return with great alarm. People know how chaotic his time in office was. They saw various foreign leaders wrap then President Trump around their finger. They saw how vulnerable and susceptible he was to calculations about personal self-interest and self-dealing, and how disinterested he was in preserving our alliances.”

A popular parlor game in Washington has been to predict who Trump could choose for his cabinet amongst a dwindling set of foreign policy experts still willing to work with him. Within the Republican party, there is a broader split between two camps supporting Trump: those who think that US should embrace a muscular, hawkish foreign policy traditional to Republicans, and those who believe that the US should occupy a more isolationist position.

“We are not going to be the world’s policeman,” said Elbridge Colby, a deputy assistant secretary of defense during the first Trump administration, in an interview this week with the New York Times. “We have to understand that, because for the first time in more than a century, we are not clearly the world’s largest economy. And we’re definitely not the world’s largest industrial power.”

With Israel expanding its war into Lebanon in the weeks before the election, there is considerable doubt that the White House under Harris or Trump will be prepared to meaningfully rein in Benjamin Netanyahu and find a diplomatic solution to the conflict.

“I think America is weak,” said Yossi Melman, an Israeli journalist who specialises in security affairs, and is co-author of Spies Against Armageddon: Inside Israel’s Secret Wars. “America is losing its influence.”

Washington under Biden was unable to compel either Iran or Israel to the table, he said. A Trump presidency would be “extremely unpredictable”, he added, but although Trump had suggested he would allow Israel to “finish what they started”, his own troubled relationship with Netanyahu could interfere.

“His record is not very pro-Israeli in the Netanyahu sense,” said Melman. “I’m not ruling out that if [Trump] is a player, then he would just say: ‘Fuck off.’”

At the same time, there is considerable skepticism that a Harris administration would meaningfully alter Biden’s policy of support for Israel even while attempting to broker a ceasefire. The vice-president has spoken out more forcefully on her sympathy for the plight of Palestinians, but at the same time she has rejected a potential arms embargo against Israel that could be used to put diplomatic pressure on the Netanyahu administration.

“If Trump is elected, Netanyahu’s margin for maneuver will expand,” said Aaron David Miller, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, focusing on US foreign policy in the Middle East. “If Harris wins. I don’t see much of a change in US policy anywhere… it’s hard to imagine, unless there are ready made opportunities, not just crises, that you know she’s going to be prepared to wade in any in a way that’s different than Biden.”

It’s a pattern that has repeated itself with the US relationship with Israel for decades now. Miller recalled when Barack Obama entered office in 2009 that he was told by an official that this time was “going to be different.”

“This person said, you’ll see, particularly with Israel, he’s not going to deal with Netanyahu the same way,” he said. “You’ll see it’ll be tougher. It’ll be stronger. None of it happened and I doubt any of it’s going to happen now.”

As those conflicts rage on, a number of prominent Republicans have called for the US to refocus its attention toward China, with some saying Trump should divert resources from the conflicts both in Russia and in the Middle East toward controlling China’s rise.

“The existential threats to America, to our existence, to our kids, how they live, to our grandkids, come from one place. It’s the Chinese Communist party in Beijing. It’s Xi Jinping and his ambitions,” said Robert O’Brien, Trump’s former national security advisor who is said to be seeking a position in a potential Trump administration.

Some foreign officials have said that the potential for pedigreed officials such as O’Brien to return to a potential Trump administration could help control his unpredictability.

But new reporting has suggested that Trump has been freelancing his own foreign policy, carrying on private conversations with foreign leaders such as Putin in the years when he was out of the Oval Office. The Wall Street Journal this week reported that Elon Musk, a prominent Trump surrogate who has become his largest donor, has been in “regular contact” with Putin since late 2022. At one point, Putin reportedly asked Musk not to turn on his Starlink satellite network over Taiwan as a personal favour to Xi Jinping. Both men have denied the reports.

Taken together, it suggests that Trump’s policies in a potential administration may largely be shaped by just the candidate himself.

“Trump has taken positions on nearly all foreign policy issues that are really heterodox and run counter to decades of bipartisan US foreign policy expectations,” said Weiss. “So if Trump comes back, the general expectation is that the quality of his leadership is going to be more chaotic and more disruptive than it was eight years ago. Because he seems bent on being his real self, as opposed to the version that was hemmed in by traditionalists when he came into office.”